IB Macreconomics

Real World Examples (RWE's) Debt

What's wrong with a little (or a lot) of debt?

Discuss the view that government debt is likely to impact economic growth [15]

First of all, it’s probably worth looking at the potential problems and link of debt to economic growth

Interest rates rise: borrowing costs rise in line with interest rates! Debt repayment then increase!

Reduced Fiscal Flexibility: High debt levels can restrict a government’s ‘fiscal flexibility’. With a significant portion of revenue being diverted towards interest payments, there is less available for public services, infrastructure, and other critical needs that can stimulate economic growth.

Higher debt increases risk: (and risk perception). Investors may be less willing to invest in a country where the perception of risk is high!

‘Crowding out’ when governments borrow heavily, government often obtain the money from the private sector by selling bonds which are bought by the private sector. Often the private sector will pay for the government bonds (which offer attractive interest rates) by selling corporate bonds, draining or withdrawing funds from the private sector.

Inflationary Pressures: In some cases, governments might resort to printing money to pay off their debt, which can lead to inflation. High inflation erodes the real value of money, reduces consumer purchasing power, and can increase the cost of living, thereby impacting the overall economy.

Increased Borrowing Costs: High levels of debt can lead to increased risk perceptions among investors, resulting in higher interest rates on government bonds. This makes borrowing more expensive for the government, which can limit its ability to finance new projects or maintain existing services.

Economic Instability: Excessive sovereign debt can lead to economic instability. If investors start doubting a government’s ability to repay its debt, it can lead to a loss of confidence, capital flight, and a sharp devaluation of the national currency.

Austerity Measures: To manage and reduce high debt levels, governments often implement austerity measures, such as reducing public spending or increasing taxes. Such measures can slow economic growth and increase unemployment, particularly affecting the lower and middle-income populations.

Vulnerability to External Shocks: Countries with high levels of sovereign debt are more vulnerable to external economic shocks, such as fluctuations in global interest rates or changes in global financial markets. Such vulnerability can exacerbate economic downturns and lead to prolonged recoveries.

Risk of Default: In extreme cases, unsustainable debt levels can lead to a risk of sovereign default. If this occurs, austerity measures may be needed and the country will be locked out of lending in the future, which will inhibit growth. Nobody will lend to you!

How are different stakeholders affected?

Have a look at how the effects are spread amongst key stakeholder groups.

1) Government

Unsustainable debt can severely restrict government spending. As debt grows, a larger portion of the budget is allocated to interest payments, limiting funds available for public services such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure. This can lead to cuts in social programs, affecting the quality of life and economic opportunities for citizens.

3) Business

An unsustainable debt level can deter investment as businesses anticipate higher taxes, inflation, or economic instability. Reduced consumer spending affects business revenues and profitability, leading to potential layoffs and lower capital investment.

2) Consumers

4) Financial markets

High debt levels can lead to decreased confidence among investors, resulting in higher yields on government bonds to attract buyers, increasing future borrowing costs. Credit ratings for the country might be downgraded, making borrowing more expensive and potentially leading to a vicious cycle of increasing debt.

5) International relations

Countries facing unsustainable debt may seek bailouts from international organizations, which come with stringent conditions, potentially leading to austerity measures that can further slow economic growth and affect citizens’ quality of life. Once defaulted, relations can be strained, and the defaulting country frozen out of further lending!

Does high levels of government debt guarantee a crisis?

Economists disagree somewhat, but as a rule of thumb, 80/90% debt to GDP is felt to be sustainable! After that, things could get a little complicated!

Let’s have a look at a pair of real-world examples, using Singapore and Greece for comparison. We’ll start with their respective GDP graphs to indicate how they’ve fared over the past 20 years.

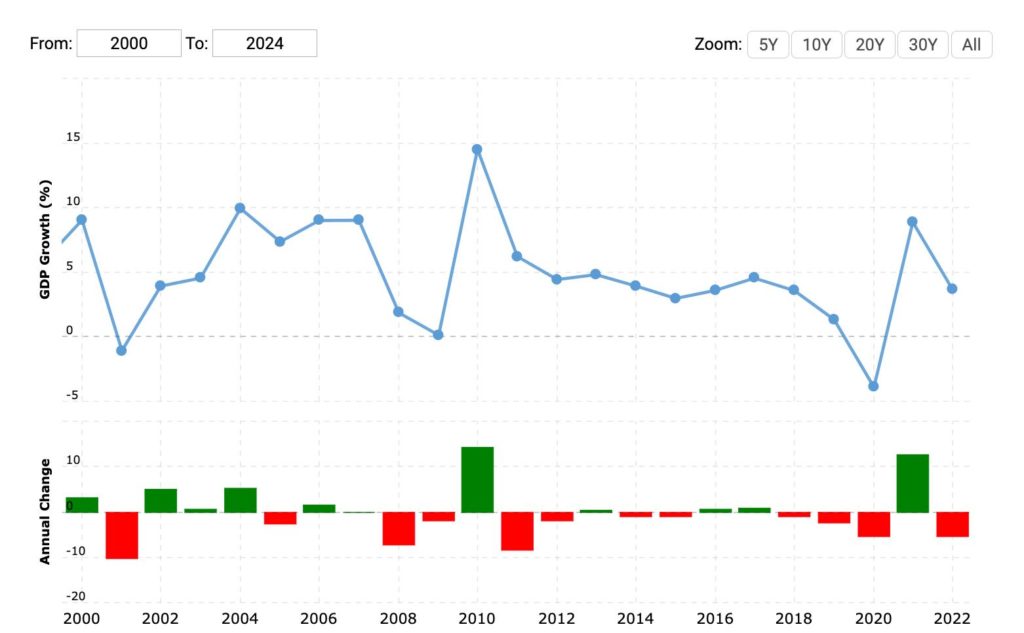

Singapore

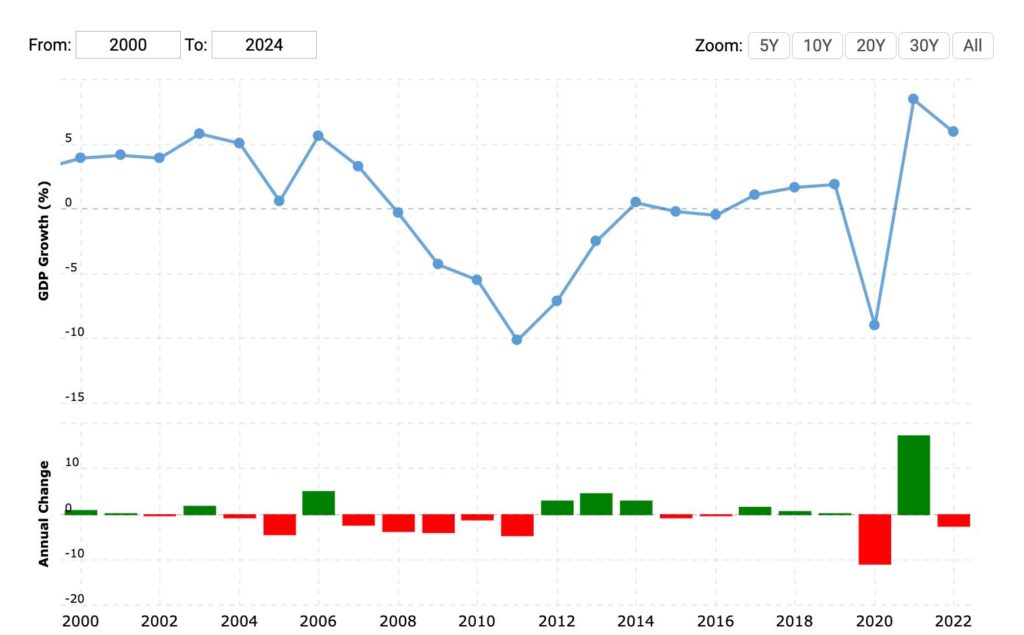

Greece

168% Debt to GDP!

How was troubled avoided?

Consistent budget surpluses have allowed Singapore to invest heavily in infrastructure, education, and technology, which bolster long-term economic growth (and push the PPC curve outwards). This in turn improves productivity and international competitiveness. Consistent budget surplus acts as a protection or insurance policy against exogenous shocks such as the GFC or Covid 19 crisis.

Strong institutional governance (is also credited), which feeds into confidence of international investors and creates a self perpetuating cycle of prosperity.

The country’s strategic location as a global hub for trade and finance also plays a crucial role! Whilst Singapore cannot take the credit for their location, they can take credit for economic policies that help to make use of the borrowing in a way that can outperform debt repayment.

The graph below indicates 22 years of economic growth. And, whist it may not be rapid, the long term average is significantly above the global 3% GDP average.

165% Debt to GDP!

What went wrong?

Greece was accused of economic mismanagement, such as high public sector wages, pensions and other social benefits, which yielded limited supply side benefits and led to successive fiscal deficits.

This spending yielded little in terms of improving productivity, supply side improvements or pushing the PPC curve outwards!

Austerity measures followed the first financial default whereby Greece failed to pay back one of its portions of a loan. Austerity measures led to deep economic contractions, soaring unemployment, and social unrest, which in turn reduced consumer spending, business investment and confidence which further stifled economic growth. A lack of growth makes paying existing debt harder to pay back!

Greece’s financial problems signalled to the rest of the world, ‘do not lend to us’, which made recovery difficult!

As problems worsened, investment (both foreign and government fell) which affected both supply and demand side! Brain drain followed as many young, highly skilled workers left in search of better prospects! This in turn had a large impact on the PPC curve and both present and future economic growth prospects!

Key differences between Singapore and Greece

The analysis of debt and economic growth are interesting. In a sense, the performance of a country seems not to be delineated by the debt to GDP ratio alone!

Debt to GDP increases the risks and problems during a crisis, but what seems to determine the performance through the crisis and recovery, wasn’t debt alone, but the wider economic framework.

For example, Singapore’s strong institutional governance has ensured that necessary economic policies are in place, even if unpopular, such as necessary taxation and spending. Greece by contrast was accused of avoiding difficult problems which led to budget deficits and poor fiscal flexibility when the GFC and Covid crises hit, which meant that recovery was more difficult.

Conclusion

A high debt to GDP is not indicative of a problem, in and of itself. However, increased levels of government debt do increase the possibility of economic problems, if a crisis occurs! The question of, ‘how will a country perform through that crisis’ is answered in this case by how well the economy is managed and therefore prepared for a crisis!